Sacred Artwork

St. Joseph in Art History

Throughout the Year of St. Joseph, we’ll be exploring the various ways St. Joseph has been depicted in Christian art and iconography.

Mosaic Decoration in the Basilica of St. Mary Major, Rome

The decoration of the Early Christian churches, and particularly of the basilicas, was mostly with mosaics. The largest series of early Christian mosaics in Rome are the panels on the triumphal arch and the nave walls of the basilica of Santa Maria Maggiore. These extensive mosaics were completed between 432-40 AD. The arch is decorated with continuous New Testament scenes relating to the early life of Jesus. Mary, the Mother of God, is shown as queen of Heaven, enthroned and dressed regally. Jesus is portrayed as a youth or young adult, not as an infant or child. On the top register, Saint Joseph can be seen to the right. Joseph is young, bearded and garbed as a Roman of status befitting the consort of a queen. Here he is conversing with the angels announcing Jesus birth and holding not a shepherds staff, but in his left hand a rod symbolizing the authority and responsibility he has just been given. In the bottom register, Joseph stands on the left side, in Bethlehem, the city of David, the king from whose descendants, traced to Joseph, Jesus was born. On the right is seen Jerusalem, the place of Jesus’ death and resurrection.

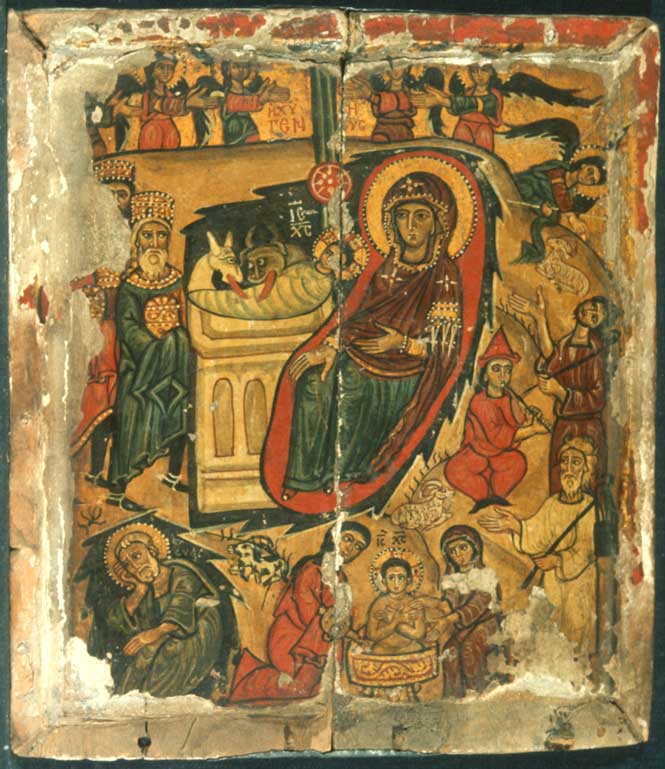

Nativity – The Sinai Icon Collection

In the Early centuries of Christianity, Saint Joseph appeared only in images of the Nativity, likely because that is where he is found in Scripture. Most of the narrative surrounding Joseph comes from the Gospel of Matthew and the traditional accounts documented in the Protoevangelium of James. Some of the oldest extant images of Joseph can be seen among the icons of Saint Catherine’s Monastery in Egypt’s Sinai. In these images, dating from perhaps as early as the 7th century, Mary is central to the scene and the animals adore the infant Christ, as angels, magi, shepherds, and maids attend our Lord, and musicians play. Saint Joseph is shown in what for centuries became his characteristic pose. He sits in the corner of the cave, chin in hand, pondering what James calls “Joseph’s Troubles” – the awesome and terrible responsibility of the care and protection of God incarnate as a human child.

Marriage of the Virgin – Giotto di Bondone (1305)

The earliest record of a formal devotional for Saint Joseph in Church comes from France in the year 800. As devotion to Joseph increased, the faithful sought details of his life beyond the sparse account found in Holy Scripture. In the 13th century, various written and oral apocryphal sources that comprised Church tradition were compiled by Jacobus de Varagine into a widely read work entitled Legenda Aurea or Legenda Santorum ( in English, the Golden Legend.) At the height of the popularity of the Golden Legend, the great Porto-Renaissance artist, Giotto completed a monumental cycle of frescoes on the Life of the Virgin For the Cappella Scrovegni in Padua. In a new vivid realism, Giotto shows us an older Saint Joseph, mature enough to be guardian and protector for the Virgin and her divine Son. As he presents himself for marriage, Joseph is depicted once again holding the rod; this time it is not a symbol of authority, but a testimony to events depicted in the Legend account. Mary came of age to be betrothed and an angel told the priest to summon marriageable men to the Temple with their rods, where a sign would be given as to which is worthy to be betrothed to Mary. St. Joseph was chosen when a dove descended on his rod just as a flower sprouted forth from it. From this point forward, the flower, most often a lily, became a standard symbol of Saint Joseph in Church art.

The Presentation of Jesus in the Temple – Fra Angelico (ca 1540)

As the sun was setting on the medieval world, new depictions of Saint Joseph and the Holy Family began to emerge. None of these works were more impactful and timeless than the warm and immediate images found in the frescoes of the Dominican painter, Guido di Pietro, known most often today as Fra Angelico.

The Presentation of Jesus in the Temple, painted between 1540 and 1542 is a fresco by Fra Angelico made for the Dominican convent of San Marco in Florence during the time when the artist was prior there. This is one of a limited number of frescoes whose composition and color confirm with some certainty that Fra Angelico executed most of the work himself. The scene is serene, but immediate with warm tones and an earthly setting lacking the gold embellishments Fra Angelico was known to use skillfully in his wealthy commissions. This scene was painted in a monk’s cell for the purpose of contemplation. Here Joseph is placed on the same visual plain as The Virgin, standing with her as husband and wife. She presents her Son to Simeon as Joseph presents the customary offering. Joseph is neither old nor young, but a fitting compliment to Mary. In the foreground just before them, Saint Peter Martyr and the Blessed Villana of the Dominican Order contemplate the scene. It is also interesting to note that the image of Joseph bears a striking resemblance to other works of Blessed Fra Angelico that are identified as self-portraits, thus suggesting that the Prior/Artist may well have looked to Joseph as a patron and example as he served his brother Dominicans.

The Adoration of the Christ Child – Alessandro Botticelli (ca 1500)

Catholic religious art has been forever shaped by a group of 15th century talents known as the Florentine School. The naturalistic style, first explored by artists such as Giotto, became the hallmark of early Renaissance Florentines including Fra Angelico, but perhaps no artist epitomized this group more than Sandro Botticelli.

Apprenticed as a youth to the Carmelite Fra Filippo Lippie, Botticelli grew up, painted, and was buried all within blocks of his birthplace. Among his many surviving religious works are a series of adorations. It is in these adorations that we find a new and different symbolic understanding for the place of Saint Joseph in Catholic iconography.

Joseph is no longer a consort-protector attesting to the Christ’s Davidic lineage, a man on the periphery caring for the animals, or simply the rightful husband of Mary as told in The Golden Legend. At first glance, this painting shows Joseph taking a nap with the Christ child as the Blessed Virgin looks on, but Botticelli imbued his Saint Joseph with a deeper symbolism. In the dual and juxtaposed images of Mary and Joseph we see an allusion to the Divine and Human natures of the child lovingly asleep between them. Joseph mirrors the needs and weaknesses of Christ’s humanity while the sinless Virgin gives adoration to the divinity of the very child she bore who is turned and presented in the image for the viewer to do the same. In this work, Saint Joseph, painted with exceptional detail and delicacy by Botticelli, the working-class son of a tanner, becomes an example of every man’s duty to God while Holy Mary demonstrates the need for us all to gaze in adoration upon Our Lord. All this was depicted at the very point in Church history when plagues and wars had brought the faithful to a greater appreciation for the value of Eucharistic Adoration.

The Adoration of the Christ Child – Fra Bartolomeo (ca 1499)

At first glance, this painting of the Madonna and Child with Saint Joseph completed during the High Renaissance seems an obvious nod to the slightly earlier work of Botticelli. Long regarded an exceptionally executed work by Fra Bartolomeo, the presence of a fingerprint on this piece recently caused art historians to change its attribution to none other than that of Leonardo da Vinci. With the 500th anniversary of Leonardo’s death coinciding with our Year of Saint Joseph, it seems fitting that we examine the subtle differences in of his treatment of Joseph. Botticelli was elder, but he and Leonardo ran in the same circles and both owed patronage to the Medici. There is no doubt that da Vinci could have studied Botticelli’s piece, but he chose instead to execute a more intimate scene. Joseph is awake and he and Mary gaze not simply in awe and wonder at the infant Christ, but with the love of parental tenderness. The child Jesus is not turned awkwardly to the viewer for adoration, but reaches lovingly toward his true mother rather than his corporal father figure. The result in no way lessons Saint Joseph, but rather makes clear the role of Mary. With a perfect eye for perspective and geometry. Leonardo depicted Christ at the point of an inverted triangle making Him the focal point of the piece. The intense black of Mary’s sleeve draws the eye to Christ, as does the angle of Saint Joseph’s staff. The lighting caries down from an opening in the heavens through the center of the scene, Illuminating Jesus. Here we see the image of a true and natural Holy Family with Christ as its center.

Saint Joseph and the Christ Child – (Cuzco School) c. 17th century

In the 16th century Christianity spread to the Western Hemisphere and this resulted in the birth of a new Roman Catholic artistic tradition based in Cusco, Peru – the Escuela Cuzquena or Cusco (Cuzco) School. Cusco was the former capital of the Inca Empire and its new artistic style’s popularity quickly spread throughout the cities of the Andes to present day Ecuador and Bolivia, lasting well into the 1700’s. Cusco was the first artistic center where European painting techniques where taught in the Americas. Jesuits introduced the fashionable art from Spain and Flanders and Andean artisans made it their own – bringing lush color, elaborate garments and rich adornment common to Incan art. We soon see their work reflecting the greater understanding of the role of Saint Joseph in the Church. Mary is nowhere to be seen in this particular 17th century work; instead we see Saint Joseph as young doting father, relishing his paternal role. For the first time, he is regularly depicted not as a peripheral character or supportive reflection of Mary, but rather at the center of the work, with his own rich royal garb in keeping with the Christ child’s regal status surrounded by regional flowers. The bright red sandals worn by the Christ child are the same as those worn by indigenous Inca elites. St. Joseph was a figure with whom new Christian believers could relate and his devotion grew throughout Europe and the West as faithful fathers turned to him for intersession on behalf of their families and marriages. Increasingly, Joseph was also seen as the patron of a “good death” with the image of his peaceful passing with Christ and the Virgin Mary at his side.

The Death of St. Joseph – Giuseppe Maria Crespi (ca 1712)

After the Council of Trent, (1545-1563) the Church entered a period often referred to by historians as the Counter-Reformation. While Calvinists were removing public art, even religious art, from their communities, the Catholic Church continued to encourage and promote art with an increasing eye towards its content. The great artistic masters of high Renaissance Europe frequently alternated between Classical and Ecclesiastical subjects, allowing attributes of each to bleed into the other. After Trent, the Church encouraged a new focus on works centered on Catholic traditions, sacraments, and saints. In this time, Saint Joseph’s increasing veneration comes to the fore and a new focus is placed on his patronage of a Good Death. The epitome of this subject matter can be seen in Giuseppe Maria Crispi’s depiction of the Death of Saint Joseph. The painting, produced under the patronage of the Cardinal of Bologna, shows an aged and dying Joseph in a poor and gloomy house. His rod is at his feet and his carpenters tools are set aside, while Mary weeps. This demonstrates the ephemeral nature of our earthly life and Joseph, a devoted husband and hard worker shows no concern for its loss. His sole focus is on the face of the young Christ who offers him blessing and passage. Joseph’s peaceful passage after a life of devotion becomes the example for all who wish to succumb to the loving embrace of Our Lord

St Joseph and the Child Christ – Bartolome Esteban Murillo (ca 1670-75)

Entering the Baroque art of the 17th century, we encounter more and more depictions of Saint Joseph alone with his foster Son and apart from the Virgin Mother. Among the most popular of these works reproduced in modern times are the paintings of Spanish artist, Bartolome Esteban Murillo. In a frequent departure from what had become the convention of the Italian Renaissance, Murillo often paints a younger, dark-hired Joseph lovingly interacting with the Christ child. Known for his natural portrayals of children and family life, Murillo shows a Joseph adoringly gazing at the babe while Jesus holds a miniature version of Joseph’s flowering staff, thus symbolically linking Him, though Joseph, to the lineage of David. The Infant, painted in the burred, soft-edged brushstrokes of the era, gazes in the direction of the viewer with an awareness the belies His age. The halos are gone, and Joseph protects the divine child, in his full, vulnerable, humanity, so necessary for our redemption.

The Holy Trinity with Saints Joseph and Francesco di Paola – Giovanni Antonio Pellegrini (ca 1727)

Joseph has now reached a level of devotion that sees him holding his own among the Communion of Saints as found in this 18th century oil painting by Giovanni Antonio Pellegrini; Entitled: The Holy Trinity with Saints Joseph and Francesco di Paola. In this work, we see the Trinity shown in what had become the standard western fashion – the Son, holding the cross, sits at the right hand of the Father with the Holy Ghost as a dove between them. No Virgin Mary and no infant Jesus are shown. Saint Francis di Paola is kneeling in rapt adoration while Joseph, instead holds a small stalk of flowers and assumes a pose as earthly father/teacher mirroring nearly the exact appearance of God the Father in Heaven above him. His importance has taken him beyond his job as caretaker for the infant Christ to a potent heavenly intercessor for the faithful who seek his assistance.

Rest on the Flight to Egypt – Luc-Olivier Meson (Ca 1880)

With the advent of inexpensive books, holy cards, and the mass pulp paper production of the late 19th century, we see an explosion of cheap, popular, manufactured religious images and with them endless saccharine drawings of the Holy Family by countless unknown artists. Since the Enlightenment, artists no longer felt compelled to earn their reputations with the requisite religious pieces. When an artist chose a scriptural theme, it was as often to plumb it for psychological or political symbolism. It is into this atmosphere that in 1879, the French artist Luc Oliver Merson produces the striking depiction of Rest on the Flight to Egypt. Here we see Joseph having come full circle. The Holy family are exhausted refuges with Mary asleep in the arms of Sphynx. Refuges from persecution at the hands of Herod, Joseph sleeps on the edge of the light of a dying campfire. Much like the post Napoleonic archeologists of his day, Merson traveled to Egypt to depict the world of Christ’s life in accuracy and realism. Though Merson was an academic artist, he gently returns the Holy Family to a chiaroscuro produced by the light of the Christ Child and the halo of his mother’s sanctity. Regarded in religious circles as somewhat scandalous for its depiction of the profane sphynx, the image was welcomed and accepted by the public and has come to be adored for its realistic juxtaposition of the grandeur of a dead religion eclipsed in the holy light of a tiny babe. Catholic immigrants of the era, having witnessed modern persecutions saw the beauty and reality of the protection of the exhausted Joseph in their own fatherly duties.

The Birth of Jesus – Monks of Conception Abbey (1893-1897)

The Beuronese style of art began in the 19th at a Benedictine monastery in the town of Beuron, Germany spreading to Czechoslovakia. Later, monks trained in this style moved to the United States. Beuronese art was undoubtedly influenced by Egyptian art and it in turn influenced what later came to be known as the Art Deco style. Several different principals formed the canon of the Beuronese technique taught to the monks, with geometry heavily used in determining the proportion of the figures. A religious philosophy was at the basis of these works – namely that there is a connection between beauty and truth, and both are revealed by God. It has been suggested that these pieces may make up the last major artist movement of the modern era attempting to make a continuous connection between beauty, truth and the necessary role of these in liturgy and prayer. Here we see a Beuronese nativity painted by the Monks of Conception Abbey in Missouri. Saint Joseph, depicted with the symbolic attributes we’ve come know, kneels in humble adoration. He is the mirror image of the Virgin and like her he worships in purity and faith. Above him are the angels bearing the message, Gloria in excelsis Deo. Stylized and idealized, this image speaks to our developed understanding of Joseph as a guardian with a profound and important role. Artistically akin to the earliest icons, these much more recent depictions see Saint Joseph as a fatherly figure, intercessor, and protector of the Church.